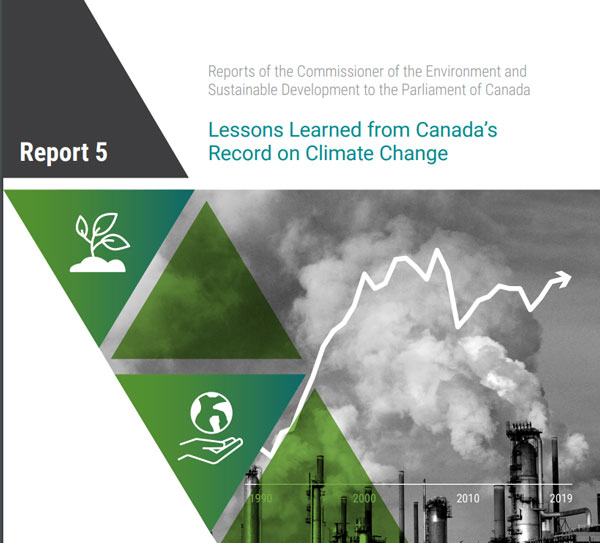

Canada performs the worst of all G7 nations when it comes to climate change, says a new report from Canada’s environmental watchdog.

After years of effort to reduce emissions, Commissioner of the Environment and Sustainable Development Jerry DeMarco, writes Canada has some lessons that must be learned.

DeMarco tabled his reports in the House of Commons this month. They document 30 years of federal government commitments to reduce greenhouse gas emissions which have led to an increase of more than 20 per cent in emissions since 1990. The report, which is not an audit, also offered a series of lessons the country can glean from its effort.

“Canada was once a leader in the fight against climate change. However, after a series of missed opportunities, it has become the worst performer of all G7 nations since the landmark Paris Agreement on climate change was adopted in 2015,” said DeMarco. “We can’t continue to go from failure to failure; we need action and results, not just more targets and plans.”

Leadership and co-ordination

One of the lessons the report stressed for was stronger leadership and co-ordination to drive progress toward climate commitments

According to the report, this point is especially true of the oil and gas sector. The report explained some responsibilities relevant to climate change fall under provincial and territorial jurisdiction and climate actions are often subject to divergent regional interests.

For example, Alberta, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland and Labrador produce 97 per cent of Canadian crude oil. In addition, Alberta and British Columbia account for 97per cent of Canada’s production of natural gas and natural gas liquids.

“Canada’s climate goals cannot be met without taking the oil and gas industry into account, but the debate about fossil fuel development risks both partisan and regional division,” wrote DeMarco.

“Experts that we interviewed told us that Canada needs to depolarize the climate change discussion to move the debate from whether the country should significantly reduce its emissions and toward a discussion on how emissions should be reduced.”

The report also cited the federal government’s investment in the Trans Mountain Pipeline Expansion while trying to position itself as a global leader on climate action as an example of policy incoherence.

Competing pressures

Another lesson the report highlighted was that Canada’s economy is still dependent on emissions-heavy sectors.

“Because of these competing pressures, aggressive climate policies face not only climate skepticism, but also pushback from powerful industry interests and voter concerns about higher energy costs and economic losses caused by a transition to cleaner sources of energy. Partly because the provinces and territories have very different economies and priorities, climate change has been a polarizing regional issue in Canada,” wrote DeMarco.

The report cited Natural Resources Canada’s Energy Fact Book 2020–2021 which shows the oil and gas industry directly accounted for more than 5.3 per cent of the country’s gross domestic product in 2019, growing to 7.8 per cent when accounting for indirect contributions.

It directly employed nearly 176,500 people and indirectly employed 422,500 people in 2019. The sector also employs 10,000 Indigenous workers. The industry is also the largest greenhouse gas emitter in Canada, accounting for 26 per cent of Canada’s total emissions in 2019.

“Because of these competing pressures, aggressive climate policies face not only climate skepticism, but also pushback from powerful industry interests and voter concerns about higher energy costs and economic losses caused by a transition to cleaner sources of energy,” wrote DeMarco.

He noted the good news is other countries have successfully navigated this through long-term funding, diversifying energy production, having a national energy strategy and shielding workers and communities that could be hurt by the transition.

Prioritizing adaptation

According to the report, the increasing costs and impacts of extreme weather events and the inability to reverse some of climate change’s effects make investing in resiliency a must.

The costs per disaster have increased drastically as well, jumping 1,250 per cent since the 1970s. For example, the devastating 2016 wildfires in and around Fort McMurray, Alta. necessitated the evacuation of over 80,000 people and incurred $11 billion in economic losses. Loss of property is another concern because an estimated 10 per cent of Canadian households are at very high risk of flooding.

“Compared with the high costs of cleaning up disasters after the fact, investing early in adaptation measures avoids losses and generates significant economic, social and environmental benefits, such as through reducing risk, increasing productivity and driving innovation,” wrote DeMarco.

He cited a 2019 report which found that a global investment of $1.8 trillion in early warning systems, climate-resilient infrastructure, improved dryland agriculture crop production methods, global mangrove protection, and more resilient water resources from 2020 to 2030 could generate $7.1 trillion in total net benefits.

The report cited several other major lessons, including the international crisis climate change poses, the need for enhanced collaboration and the lack of strong plans to address the issue. A link to DeMarco’s full report can be found .

Follow the author on Twitter .

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed