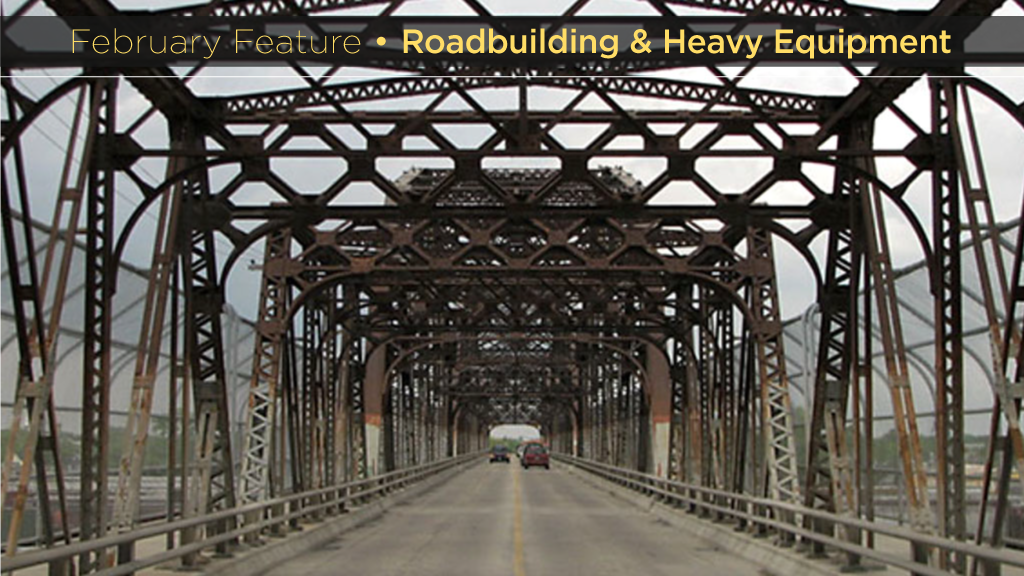

The Arlington Bridge, which extends over Winnipeg’s sprawling Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) freight yards and is almost three square kilometres in area, was recently closed by the city until further notice.

The move followed a thumbs-down assessment by city engineers, who are studying whether to repair the bridge and extend its life or to close it forever and possibly demolish it instead.

The 113-year-old structure is deteriorating rapidly, the city says, making it unsafe for traffic.

Commuters, including pedestrians and cyclists, who need to get from one side of the yards to the other can go under them by either of the Main Street or McPhillips Street underpasses, or over them on the Salter Street bridge.

The CPR freight yards separate the north end and the west end of the city, both of which are old inner-city neighbourhoods.

The Arlington Bridge was shut down after engineers found that corrosion in the steel-truss structure had accelerated and had got to the point where they believe annual safety repairs are no longer enough.

The bridge has been a feature of the city’s modest skyline for more than a century.

The 2,155-foot-long bridge, the longest in Winnipeg, was built in 1911.

Controversy has dogged the bridge for years. The first calls to have it demolished and replaced with something better came in the late 1940s.

In 1967, city council was told the bridge was approaching the end of its useful life.

The city has been talking about replacing the bridge since 2011, but any plans for a new structure have been put off in favour of making repairs.

The most recent engineering assessment is looking at the possibility of repairing the existing structure to extend its life for another 25 years.

The answer to “what happens next?” could come as soon as the end of February. Until then the bridge remains closed.

Winnipeggers who are concerned about what the future holds for the Arlington Bridge were disappointed to find out that the city’s recent proposed multi-year budget hadn’t put aside any funding for it.

The Journal of Commerce spoke recently to several Winnipeggers about the bad-luck bridge.

City Coun. Ross Eadie, who represents the north end Mynarski ward, says the Arlington Bridge was well used by people who live in his part of town.

“They benefited the most from a fully functional bridge,” says Eadie. “Many of them used it to commute to jobs at the health sciences centre and other parts of the west end.”

Jino Distasio, professor of urban geography at the University of Winnipeg, says although the bridge isn’t a critical transportation artery, it is important to the people who live in the north and west ends who use the bridge regularly.

“In addition, the Arlington Bridge has a unique position in Winnipegger’s psyches, because it goes over the freight yards that divide the city physically and symbolically,” says Distasio.

Christopher Adams, adjunct professor of political studies at the University of Manitoba, says moving the freight yards from its current central location to the outskirts of the city gets discussed from time to time.

“Relocating the yards is a possible solution to Winnipeg’s inner city infrastructure problems,” says Adams. “But it would be enormously expensive, especially for a cash-strapped city and province. Who else is going to pay for it?”

Winnipeg historian Christian Cassidy says people either love or hate the Arlington Bridge.

“The bridge matters,” says Cassidy. “It’s a neighbourhood bridge which is used by local residents, many of whom don’t have a car. With the bridge out, it means a half-hour detour for them to get across the yards.”

Cassidy says the infrastructure needs of the inner city are being trumped by those of Winnipeg’s suburbs.

“I hope that when the engineering report is released, at a minimum it recommends the bridge be kept open for pedestrians and cyclists,” he says.

University of Winnipeg professor of political science Aaron Moore says although the bridge closure won’t have much of an impact on most Winnipeggers, it is a black eye for the entire city because it reveals the poor state of its infrastructure.

“Recently it was announced in the proposed city budget there are plans to close down many wading pools and swimming pools, so it’s not just the Arlington Bridge that’s in danger,” says Moore. “The city and the province don’t have enough money to do everything that needs to be done in Winnipeg.”

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed