As drug toxicity deaths in Western Canada continue to break records, doctors and treatment experts explain how thinking has evolved on treatment and what the construction sector can do to help save lives.

Sandra Allison, a physician and medical health officer for Island Health, explained a monumental shift needs to take place on how society views substance use.

Men, ashamed of their substance use, are driven to use alone and the legal status of drugs means they are using untested, unsafe substances that can kill.

This is the common scenario for a drug death.

She explained this means adopting a harm-reduction approach rather than a prohibitive one.

Seatbelts to minimize injuries during an accident and condoms to prevent the spread of sexually transmitted diseases are both examples of widely accepted harm reduction strategies.

“We should try to support access to any life-saving treatment in the same way as insulin for a diabetic,” said Allison. “In situations where people are dying from a toxic drug supply, it is literally a no-brainer. Safe supply saves lives and that’s why we should do it.”

Allison believes substance use has been unfairly stigmatized while treatment for other harmful behaviours like overeating, smoking, gambling and drinking alcohol are far more accepted.

“I just wish society would get a broader message of addictions and where they come from,” said Allison. “We know a lot of issues arise from childhood and lots of things pile on to people in life. We have to figure out how to support youth.”

She supports developing more policies where safe substances are available and medical professionals can supervise their use. Once that connection is made with the user, officials can work with them to reduce harm, keep them safe and embark on a care pathway.

In the construction sector, Allison urged employers make changes. First, this means creating a safe and non-punitive environment.

“We need to accept that humans work for us and they come with all the problems of being human,” said Allison. “There is no perfect worker. We need to try to understand that they are the bottom line. You are losing capacity, knowledge and skills to something that is preventable. As an employer you should want to do everything you can.”

Second, work needs to be done to break down societal norms of masculinity that prevents many from asking for help.

“In society we are groomed by the media to have a certain perception of how men behave and what they look like,” said Allison. “We need to break down those society concepts by offering more diversity. That would allow more people to express themselves healthfully. Because we are so constrained by these images that are fed to us in society and culture in the trades, it leads to people being mentally unhealthy.”

One of the major recent pushes by Island Health has been a campaign to connect men in the construction sector with lifesaving resources. Last year in the Island Health region, 263 people died from illicit drug toxicity — 225 of them were men and 126 of them were in a private home when they overdosed.

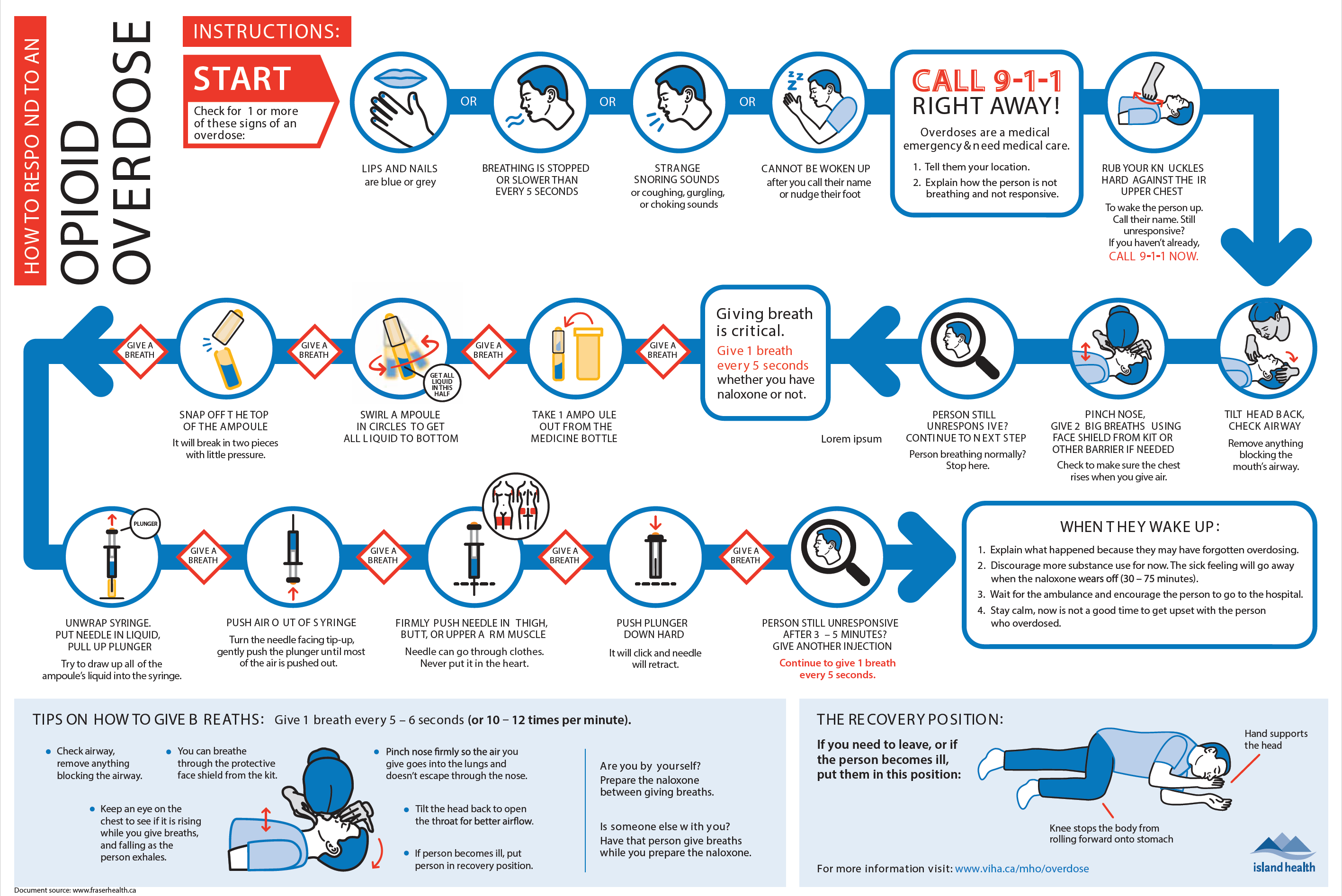

The campaign encourages users to have someone around who can administer naloxone or call for help. It advocates for testing drugs, using a small amount to start, or accessing online resources such as the Lifeguard App or the National Overdose Response Service prevention hotline (1-888-688 NORS [6677]). Island Health also operates supervised consumption or overdose prevention services in many communities in the region.

Vicky Waldron, executive director for Construction Industry Rehab Plan (CIRP), explained her organization has experienced a major shift over the years as more research has been done on addiction, substance use and treatment.

The organization was founded in the 1980s in response to the growing need to address substance use issues in the unionized construction sector. The program grew from a referral service into offering its own direct treatment. Originally it provided Alcoholics Anonymous-style 12 Step programs that evolved into a Minnesota Model where the key focus was on abstinence.

In 2016, this approach was gutted in favour of a biopsychosocial model, an interdisciplinary model that looks at the interconnection between biology, psychology and socio-environmental factors.

“It recognizes that substance use is incredibly complex,” said Waldron. “It is not just about the physical dependency. If that was the case we would just purchase an island, leave people there for a few weeks and bring them back and there would be no addiction.”

Waldron said if biology, psychology and socio-economic factors are not all addressed, success is far less likely. Much like Island Health’s thinking, CIRP adopted an approach that embraced harm reduction instead of abstinence.

“It can be very contentious,” said Waldron, who explained most peoples’ perception of harm reduction is giving out needles. “It is probably one of the most contentious topics in health care. Harm reduction at its basis is about reducing the harms associated with substance use. This takes into account that not everyone is ready for abstinence. By doing harm reduction, we don’t exclude folks who aren’t quite ready to quit yet.”

Waldron said this opens programs up to people working on using less substances and who are looking for a pathway out. Most importantly, it keeps people alive. This includes tapering off usage, developing safety strategies, training family and friends with Naloxone kits and more.

“I cannot help you if you are dead,” said Waldron. “I don’t think I have ever met anyone suffering from chronic substance abuse who enjoys that lifestyle. It is a difficult and painful lifestyle.”

The other biggest strategy CIRP employs is reducing stigma.

“That is one of the biggest barriers for construction workers and it’s not even up for debate,” said Waldron. “We have enough data. It categorically prevents people that might want to come forward from getting help. They want to come but stop because they know there is so much stigma associated with substance abuse. The truth is we can help folks and it’s often these extraneous variables that stop people from coming forward.”

Waldron explained the group’s largest bang for the buck isn’t direct treatment, it is on prevention and promotion so workers can recognize an issue early and not be ashamed to get help.

“We don’t want people coming after the wheels have completely fallen off,” she said, noting this has been especially true during a pandemic, which historically causes mental health and substance use issues to spike.

The group recently produced a webinar that educated the industry about the collision of two pandemics: substance use and COVID-19.

“This collision has had a devastating impact on construction workers,” she said.

The solution starts with employers. Waldron explained she often hears from employers eager to help but unsure of what to do.

“Create space and an environment for conversations and then know where to refer people,” she said. “You don’t have to be an expert. You just have to refer. We do a lot of training around that. We can talk to you about setting up mental health committees and leading from the top down.”

Waldron said this is the largest impact employers can have on the substance use and mental health crisis.

“That sends the message that it’s OK,” said Waldron.

Follow the author on Twitter .

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed