I usually write the monthly Nuggets report in bullet point form, but this time I’m going to be expository, since I’m essentially trying to carry forward a proposition.

Can inflation be your friend? Surprisingly, there are ways in which the answer is yes.

Can inflation be your friend? Surprisingly, there are ways in which the answer is yes.

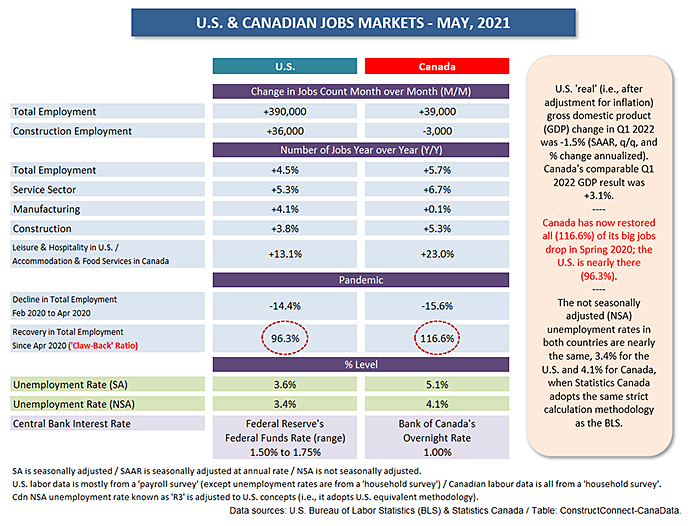

The economy is currently experiencing a severe shortage of labor. According to the Job Openings and Labor Turnover Survey (JOLTS) there are 11.4 million open positions in the U.S., while the latest Employment Situation report says there are only six million people unemployed.

Over the past two years, many elderly workers who were confronted with a job loss or found the adjustments needed to stay employed too bothersome, stepped into retirement earlier than they might have otherwise. Their planning undoubtedly indicated that a certain level of savings and pension or other income would allow them to live comfortably.

The year-over-year Consumer Price Index increase of +8.6%, and the cost of gasoline at an average of $5.00 per gallon, have come as severe shocks. Inflation, which has been mainly slumbering for decades, has woken up and is now stalking the land.

Heated up inflation threatens to take much of the fun out of retirement. Travel, entertainment and simple day-to-living all come with heftier price tags. Returning to the workplace for a while longer may not be such a bad idea. And for those who have been contemplating more leisure hours, it’s leading to a reevaluation.

Consequently, for those employers with significant holes in their staffing, inflation is helping them with the retention and re-hiring of older, and often highly skilled, workers.

Also, to the extent inflation is resulting from supply shortages, it’s giving rise to capital spending plans. There have been announcements about new multi-billion-dollar steelmaking plants (e.g., U.S. Steel in Arkansas and Nucor in Virginia). Likewise for computer chip and wafer manufacturers. Intel, Texas Instruments and Samsung have broken ground, or are planning, new production plants that, in dollar terms (e.g., as much as $30 billion; approximately half for equipment and half for construction), dwarf the previous largest individual undertakings by traditional manufacturers (e.g., a giant sawmill) or even power utilities (e.g., a nuclear plant).

There are further aspects to inflation that lead in interesting directions. What isn’t being talked about much yet is the interconnectedness between rapid price increases and substantial wage gains.

According to May’s Employment Situation report, the hourly and weekly year-over-year compensation hikes for all jobs economy-wide were +6.5% and +5.8% respectively. For construction workers, the corresponding climbs were +6.3% and +7.1%. Those are sizable jumps, way about their historical norms in the +2.0% to +3.0% range.

Thanks to the rush of inflation, plus an improvement in their leverage vis-à-vis management, workers have been able to ask for or demand higher wages. Prior to the pandemic, workers were more fearful for their ongoing employment, given that sending jobs to cheaper workforces overseas was commonplace. International supply chain breakages, however, have exposed some of the dangers of such globalization and a trend is underway to restore jobs at home.

Union negotiations with employers are, therefore, taking on a different tone. The balance of power has shifted more in labor’s favor, and this carries implications for both higher wages and even more upwards pressure to be exerted on prices.

But, from the perspective of management, there is an ‘out’ and it’s an obvious one, an ever-increasing resort to automation. Furthermore, and in interesting fashion, this may rescue the stock markets, once the current turmoil, which is seeing key indices sink deep into ‘bear’ territory (i.e., declines from summits to low points of -20% or more), eases up and bottoms out.

One key reason inflation was so quiet for an extended time frame was the incredible emergence of high-tech solutions applied with perhaps more sway to the services, rather than goods, side of the economy. Furthermore, services as a proportion of GDP have been rising relative to goods production.

One key reason the stock markets were doing so great, again for an extended period before the recent big drops, was stunning growth in the equity valuations of the widest-reaching high-tech firms. Everyone knows who they are: Apple, Amazon, Netflix; etc. The NASDAQ index, not so long ago, was up 1,000% compared with its last most apparent trough in February 2009.

For the moment, high-tech with a retail sector bent has stumbled mightily. But where there’s misfortune, there’s also opportunity. High-tech has the chance to show what it can do for logistics and the problem of shortages. Firms with a demonstrated ability to speed the delivery of goods through better expediting, more fulsome use of space in container crate packaging (i.e., many crates are shipped at barely three-quarters capacity), and a host of other potential innovations, will draw the attention of investors.

Negotiations currently underway with dockworkers along the U.S. Pacific coastline are a bellwether on the automation front. A main union goal is to preserve employment. To speed the offloading and onloading of cargo to meet the standards established in major ports elsewhere in the world will almost certainly require less manpower to be replaced by more smart equipment and robotics.

Let me close this month’s Nuggets report with a few more observations on the labor market situation, this time as it pertains to the construction and manufacturing sectors.

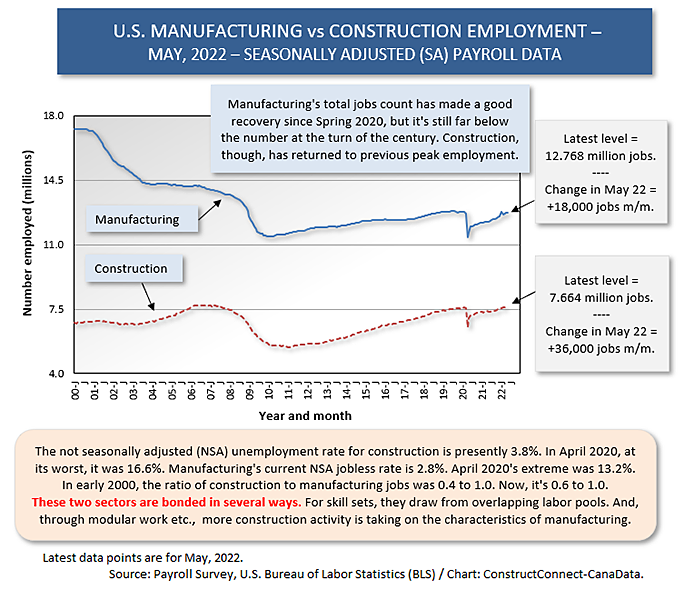

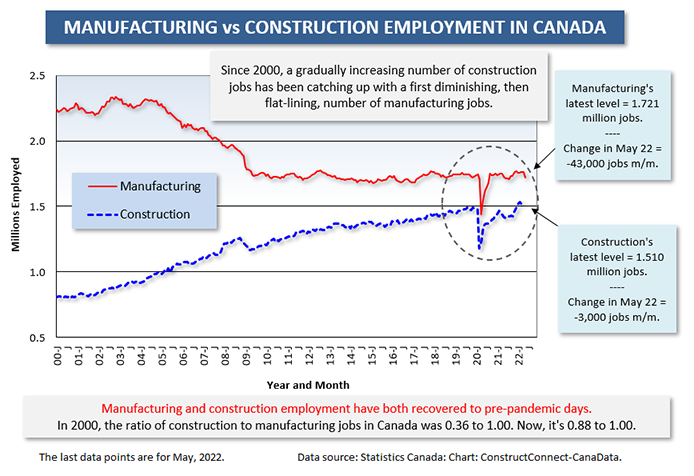

Regular readers may wonder why I’ll often mention metrics for manufacturing at the same time as I’m discussing construction. It’s because there are several points of connection between the two sectors. First, there’s considerable overlap of the labor pools from which they draw workers. Skill sets valuable for and favored by the one are often transferable, with minimal additional training, to the other. Second, while transition phases have been uphill slogs, more construction work is becoming modular, meaning it’s taking on the characteristics of manufacturing.

The last point above notwithstanding, the tendency for the total number of construction jobs in the economy to be catching up with the total number of manufacturing jobs is far more pronounced in Canada (Graph 3) than in the U.S. (Graph 2). In both countries, in the 00s, there were big declines in manufacturing employment due not only to offshoring of work, but also on account of widespread automation. There’s that word automation again. The degree to which the number of jobs in construction and manufacturing converge in the future may well hinge on their relative speeds of high-tech process implementations.

Table 1

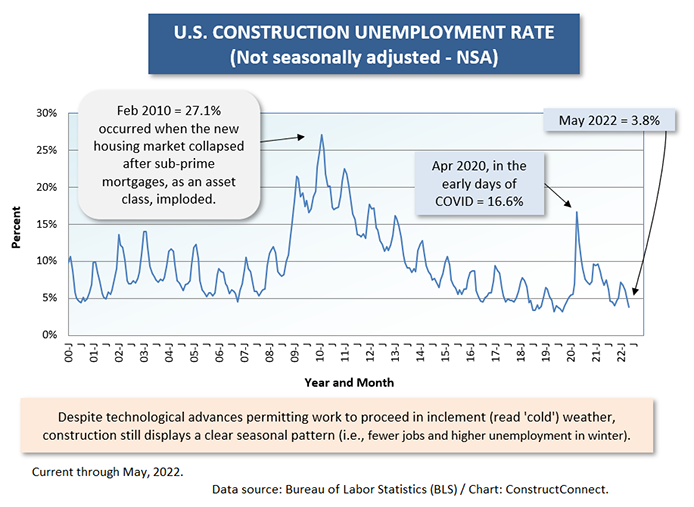

Graph 1

Graph 2

Graph 3

Alex Carrick is Chief Economist for ����ӰԺ. He has delivered presentations throughout North America on the U.S., Canadian and world construction outlooks. Mr. Carrick has been with the company since 1985. Links to his numerous articles are featured on Twitter��, which has 50,000 followers.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed