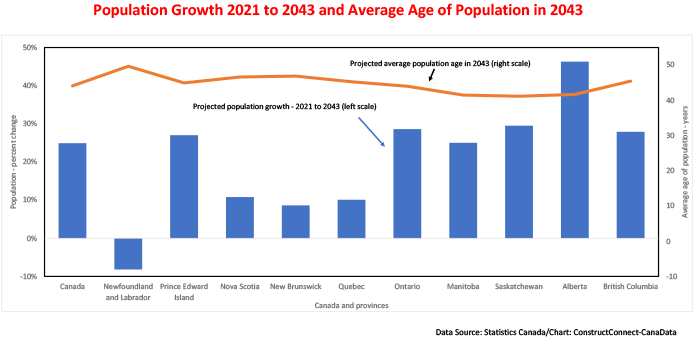

Fueled almost totally by sustained strong growth of net international migration, Canada’s population, currently just over 38 million, is projected to grow by 25% to reach 48 million by 2043. This outlook was released by Statistics Canada last month and it is the agency’s medium estimate, halfway between its high projection of 52 million (+37%) and its low projection of 43 million (+12%). The used to derive its median population projection are available on its website.

International immigration to play key role out to 2042

Let’s put the degree to which international immigration is projected to contribute to the increase in total population in perspective. Based on the federal government’s planned permanent admissions targets published on February 14, 2021, and assuming they are extended beyond 2024, 9.5 million individuals are expected to become permanent residents of Canada over the next 22 years. That will be just under twice the 4.9 million inflow of immigrants between 1999 and 2021. ��

Going forward, Statistics Canada projects that the ‘natural’ increase, in the form of births minus deaths, will add just about one million. The number of permanent residents admitted to Canada will likely get a boost this year and next due to the recent inflow of Ukrainian refugees who were initially admitted under the Canada-Ukraine Authorization of Emergency Travel program and who, after living in the country, decide to apply for Canadian citizenship.

Alberta to outpace British Columbia in interprovincial migration

After losing 50,000 residents to other provinces over the past seven years, Alberta’s vastly improved economic prospects are projected to draw in +373,000 interprovincial migrants over the next 22 years.�� The intakes for British Columbia and Nova Scotia are projected to be +274,000 and +19,00 respectively. Provinces likely to lose individuals to other provinces include Quebec (-187,000), Manitoba (-162,000), and Ontario (-142,000).

Average age of population shifting higher

The population projection highlights several key developments. First, as many are already aware, the average age of the population is going to continue to steadily rise over the foreseeable future because of the aging of the baby boomer generation, born between 1945 and 1962. This aging of the population is exacerbated by the steady gradual decline in the fertility rate (i.e., the average number of children a woman has during her lifetime).��

In 1990, the average woman bore 1.9 children. However, by 2019 the rate had fallen to 1.47 and as a result of the onset of COVID-19, it dropped to 1.40 in 2020. Over the next 22 years, Statistics Canada assumes the fertility rate will gradually trend up to 1.59 but remain below the 2.1 figure which is generally considered optimal, since it results in a stable population over the long term. ��

By 2043, Newfoundland will have the oldest population, Saskatchewan the youngest

As noted above, the average age of the population as a whole is trending gradually higher.�� However, one province is aging considerably faster than the others�� ̶ ��Newfoundland and Labrador, where the average age of the population (currently 45.2 years) is projected to hit 49.7 years in 2043. The major factors contributing to this disproportionate degree of aging include the province’s low birth rate, a steady exodus of individuals to other parts of the country, and a slowdown in the inflow of individuals from other countries. On the flip side, Saskatchewan’s population is projected to age less than the other nine provinces over the next 22 years because it has the highest rate of natural increase in the country.

Key takeaways

What are the key implications of this population forecast?�� From our perspective, there is little doubt that an aging population is going to put a lot more stress on our health care system which is currently experiencing unprecedented wait times and is ranked 10th out of 11 high-income countries by the ��, a private foundation committed to improving health care globally.

Second, slower growth of school-age populations is likely to depress spending on primary and secondary education in Newfoundland and Labrador, Nova Scotia, New Brunswick, and Quebec.�� However, stronger net international migration should give a boost to post-secondary and adult education in Ontario, British Columbia, Alberta, and Quebec.�� ��

As noted in Snapshot # 10, titled Failure to Engage Older Workers dims Growth Prospects, unless governments provide more incentives for aging individuals to remain in the labour force, growth-robbing skill shortages will increase in some sectors, particularly ‘accommodation and food services’, ‘administration’, ‘construction’, and ‘professional services.’

John Clinkard has over 35 years’ experience as an economist in international, national and regional research and analysis with leading financial institutions and media outlets in Canada.

Recent Comments

comments for this post are closed